Mit Wäldern das Klima retten: wie der Hype ums Bäumepflanzen entstand – und was davon übrig bleibt

Kaum beachtet von der Weltöffentlichkeit, bahnt sich der erste internationale Strafprozess gegen die Verantwortlichen und Strippenzieher der Corona‑P(l)andemie an. Denn beim Internationalem Strafgerichtshof (IStGH) in Den Haag wurde im Namen des britischen Volkes eine Klage wegen „Verbrechen gegen die Menschlichkeit“ gegen hochrangige und namhafte Eliten eingebracht. Corona-Impfung: Anklage vor Internationalem Strafgerichtshof wegen Verbrechen gegen die Menschlichkeit! – UPDATE

:

Kann Feed nicht laden oder parsen

cURL error 22: The requested URL returned error: 404

:

Kann Feed nicht laden oder parsen

cURL error 28: Connection timed out after 10005 milliseconds

:

Kann Feed nicht laden oder parsen

cURL error 22: The requested URL returned error: 404

:

Kann Feed nicht laden oder parsen

cURL error 22: The requested URL returned error: 404

Feed Titel: Wissenschaft - News und Hintergründe zu Wissen & Forschung | NZZ

:

Kann Feed nicht laden oder parsen

cURL error 22: The requested URL returned error: 404

Feed Titel: Verfassungsblog

Writing in Verfassungsblog in April 2024, shortly after the European Court of Human Rights’ (ECtHR) landmark climate judgment in KlimaSeniorinnen, Chris Hilson argued that the ‘most ambiguous and potentially contentious part of the ruling relates to the Court’s discussion of “carbon budgets” (paras. 550, 569-573).’

The context was the Court’s interpretation of the margin of appreciation – the level of deference the ECtHR will grant to a State – in the context of climate change. Here, the Court drew a distinction between the reduced margin of appreciation for States when setting ‘the requisite aims and objectives’ in respect of the State’s commitment to the necessity of combating climate change and its adverse effects, and the wide margin of appreciation States have in choosing the means designed to achieve those objectives (para. 543).

While describing the point as ‘ambiguous’, Professor Hilson ultimately concluded that ‘the [ECtHR] associates the issue of [carbon] budget setting with a wide margin of appreciation’. The purpose of the present contribution is to put the alternative view. Namely, that the setting of a particular national carbon budget represents the setting of ‘the requisite aims and objectives’ to combat climate change and its adverse effects, to which a reduced margin of appreciation applies, rather than simply being ‘the choice of means designed to achieve those objectives,’ where a wide margin of appreciation would apply (para. 543).

Professor Hilson’s analysis is based on carbon budgets being ‘used in two senses in the climate law and policy world.’ In the first sense, ‘they can, like the United Kingdom’s carbon budgets simply lay out a cap or maximum level that GHG emissions must be brought below in order to meet the climate targets that a state has set.’ In the second sense, the remaining global carbon budget associated with a particular global average temperature increase – 1.5°C, say – is calculated and then ‘divided up between states, in line with “fair shares.”’

In other words, under Professor Hilson’s analysis, a national climate target sets the aim or objective, with the national carbon budget simply laying out a cap or maximum level that greenhouse gas emissions must be brought below in order to meet the climate targets that a state has set. In our view, the relationship between climate targets and carbon budgets is such that the latter are never simply instrumental; rather, they always represent a choice between different aims and objectives.

To explain: a national climate target is typically a point-to-point comparison based on annual emissions in a country in two particular years: a baseline year and the target year. For example, in Ireland, the Climate Change Advisory Council was instructed by section 6A(5) of Ireland’s Climate Act to propose carbon budgets ‘such that the total amount of annual greenhouse gas emissions in the year ending on 31 December 2030 is 51 per cent less than the annual greenhouse gas emissions reported for the year ending on 31 December 2018’.

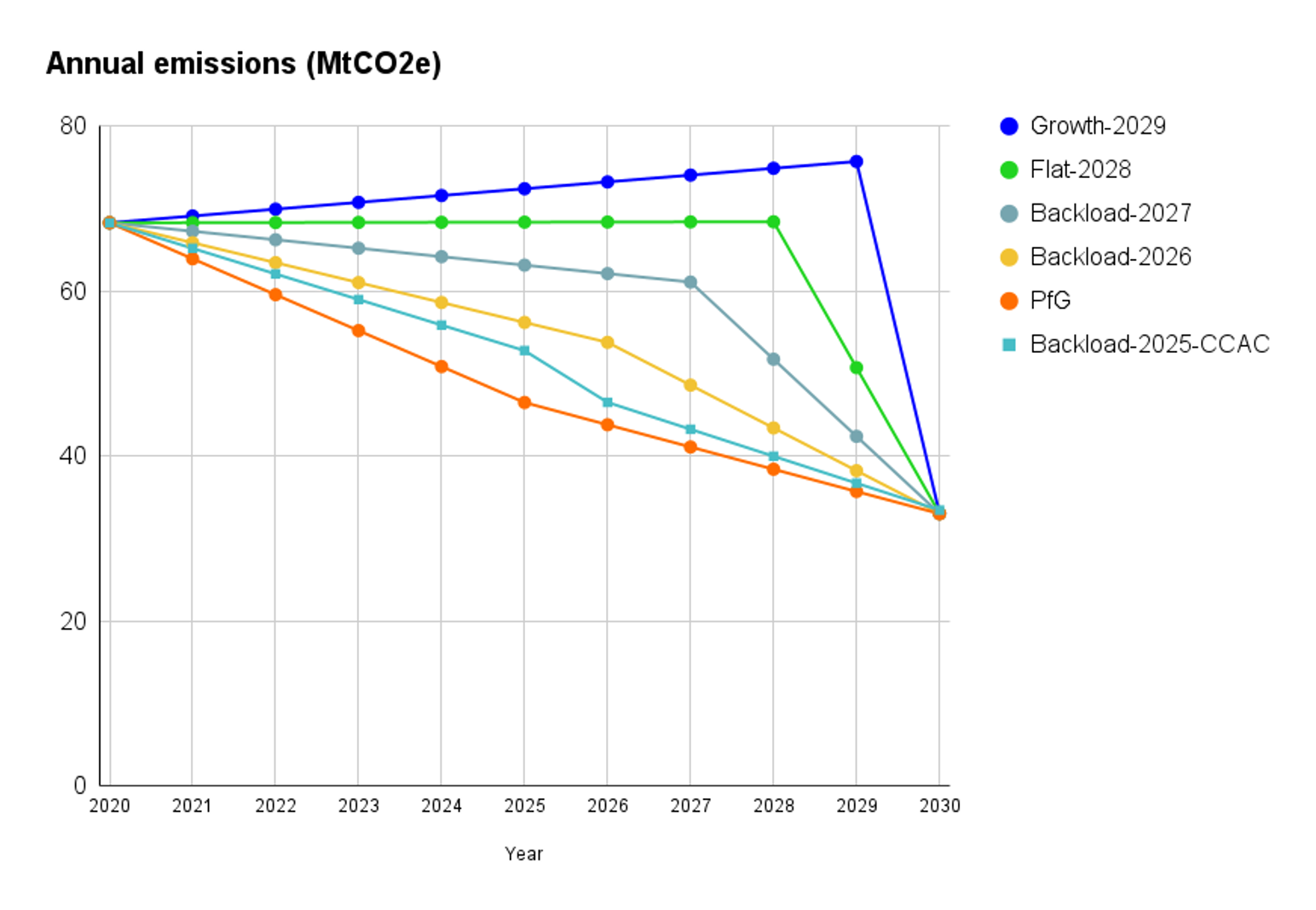

However, this instruction did not meaningfully constrain the carbon budgets that could be proposed and adopted, because there are lots of different pathways between Ireland’s annual emissions in 2018 and its annual emissions that are 51% below this in 2030, and each of these pathways has a different carbon budget associated with it. This is well illustrated by the Figure below: the carbon budget associated with each pathway (the area ‘under the line’ in each case) varies wildly.

Figure: Indicative emissions reduction pathways that are all notionally consistent with s.6A(5) of Ireland’s Climate Act (figure produced by Professor Barry McMullin).

In other words, a climate target sets the framework; it indicates what a country’s annual emissions are to be in a single year at the end of the period; it therefore sets an aim or objective in that sense, and ought to be subject to a reduced margin of appreciation per KlimaSeniorinnen. In turn, a carbon budget adopted within this framework also sets an aim or objective in KlimaSeniorinnen terms, because it is the budget that constrains the country’s contribution to climate change on a multi-annual basis. (Importantly, both targets and carbon budgets (or an equivalent method of quantification) are required by the KlimaSeniorinnen judgment: para. 550(a) and (b).)

A numerical climate target admits of and is equivocal between lots of different carbon budgets, each of which results in a different national contribution to global temperature increase. To put the point another way, the difference is between simply being given two points on a graph (the target, which compares annual emissions in two individual years) and being given the pathway that joins those two points (from which the budget can be calculated, constraining emissions for all years between the two points on the graph).

Since climate change is a problem of cumulative emissions since the beginning of the industrial revolution (Fig SPM.10 on p.18), carbon budgets are capable of constraining temperature increase in line with the Paris Agreement’s temperature goals, while climate targets alone are not. Further, in terms of the internal coherence of the KlimaSeniorinnen judgment, the alternative view, allowing States a wide margin of appreciation in the setting of national carbon budgets, would not be an approach to the ECHR that would ‘guarantee rights that are practical and effective’ (para. 545).

Thus, in our view, ‘the choice of means designed to achieve [a State’s climate] objectives’ (para. 543), to which a wide margin of appreciation applies, does not encompass the setting of carbon budgets, but rather captures policy choices such as which policies to adopt to decarbonise the energy system, how to reduce agricultural emissions, how to reduce emissions from transport, etc: these are the ‘operational choices and policies adopted in order to meet internationally anchored targets and commitments in the light of priorities and resources,’ of which the ECtHR speaks in its judgment in the context of a wide margin of appreciation (at para. 543).

It has been strongly argued by Dennis van Berkel et al in a recent contribution that, falling within the reduced margin of appreciation, KlimaSeniorinnen requires States to quantify a national fair share carbon budget that is set in relation to the remaining global carbon budget to limit heating to 1.5°C. In finding a breach of Article 8 ECHR in KlimaSeniorinnen, the ECtHR applied a quantification of a Swiss fair share carbon budget for 1.5°C (at para. 569), and rejected the argument put forward by Switzerland that its ‘national climate policy [which established targets] could be considered as being similar in approach to establishing a carbon budget’ (at paras. 570 and 360). As van Berkel et al note, ‘only a national carbon budget that is set in relation to the remaining global budget can be capable of mitigating the consequences of climate change, and thus practically and effectively protect human rights’ (cf. para. 545 of KlimaSeniorinnen). Notably, the Norwegian and Dutch National Human Rights Institutes have reached the same conclusion, as highlighted by a coalition of NGOs in their submission to the Committee of Ministers as part of the ongoing supervision of the implementation of the KlimaSeniorinnen judgment.

This obligation to quantify each country’s fair share of the remaining global budget to limit heating to 1.5°C will remain vital even as countries’ fair shares are used up (as will soon be the case for the European Union, for example, even on the ‘most lenient’ interpretation of fair share). This quantification will represent a line in the sand at a particular moment in time, calculated with reference to a particular baseline year. This will enable States to be held accountable, insofar as is possible, for their ‘carbon debt’, once their quantified fair share has run out. This seems likely to represent a new frontier in climate litigation in the not-too-distant future.

It must be recognised, however, that there are feasibility and sustainability concerns in terms of the amount of carbon debt that can be ‘repaid’ by way of net negative emissions, such that States’ primary focus should remain on rapid and deep reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. Further, the global average temperature decline as a result of net negative emissions (if achievable) is projected to be sluggish, and certain impacts will continue for many years. As the IPCC explains, ‘[i]f global net negative CO2 emissions were to be achieved and be sustained, the global CO2-induced surface temperature increase would be gradually reversed but other climate changes would continue in their current direction for decades to millennia (high confidence). For instance, it would take several centuries to millennia for global mean sea level to reverse course even under large net negative CO2 emissions.’

‘Gradually’ is the key word when it comes to reversing global temperatures: as Climate Analytics explains, ‘even under optimistic assumptions related to CDR [carbon dioxide removal] deployment and effectiveness, only about 0.05°C of global mean temperature increase may be reversible per decade.’

Barry McMullin et al thus argue that adopting a carbon debt framing ‘may help facilitate early nation-level societal discussion of whether, or how much, CO2 debt can or should be taken on, and the interaction of this with alternative pathways for earlier, deeper, mitigation of gross emissions which would allow that ultimate debt to be reduced or avoided altogether’. They conclude, ‘if large scale removal services prove difficult or infeasible to scale up, then this should prompt earlier and more severe limitation on the accumulation of CO2 debt.’

An obligation to quantify each country’s fair share of the remaining global carbon budget associated with limiting global heating to 1.5°C flows from the judgment in KlimaSeniorinnen. While there will naturally be debate about what represents a country’s fair share – the EU’s independent advisory body ESAB recently considered a range of fair share principles and concluded that the EU’s fair share has already been used up under many of these – the obligation to quantify fair share budgets should, in our view, be the subject of a reduced margin of appreciation consistent with KlimaSeniorinnen.

The post Quantifying Fair Share Carbon Budgets appeared first on Verfassungsblog.

It is a busy time in AI and copyright law. Alongside a growing body of academic analysis and media coverage, real-world litigation, possible regulatory measures, and first lower court rulings are now beginning to shape the field.

With Like Company v Google, the first groundbreaking AI copyright case is now headed to the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). In this case, a Hungarian press publisher challenges Google and its Gemini chatbot for reproducing and communicating its editorial content without authorisation.

The Court’s decision will establish the legal framework for AI’s relationship with copyright and press publishers’ rights across the EU. It will potentially reshape how generative AI systems can or cannot lawfully access, process and reproduce journalistic and other protected content. This may even fundamentally affect the economic and technical architecture of future AI development.

In this piece, I will not only try to answer the questions the CJEU will have to grapple with. I also argue that the legally correct answers expose a very serious policy problem: namely, the lack of coherent mechanisms to ensure appropriate remuneration for rightsholders. A problem that requires immediate attention by European legislators.

In Like Company v Google, a Hungarian press publisher sued Google Ireland after its Gemini chatbot generated a detailed summary of one of its articles. That piece described a celebrity’s plan to introduce dolphins to Lake Balaton; when prompted by a user, Gemini reproduced substantial portions of the protected content. The Budapest court referred four questions to the CJEU to determine whether such AI-generated responses constitute copyright infringement through unauthorized reproduction and communication to the public under EU copyright directives.

This case is not only the first case at the intersection of AI and copyright to reach the CJEU. It also reflects a broader shift that could reshape much of the information ecosystem. Generative AI is now built into search engines like Google, Bing, or ChatGPT Search and Perplexity. Instead of showing lists of websites, they increasingly offer direct answers or summaries. This redirects user traffic. Instead of clicking on links, users may increasingly only read the AI-generated summaries. Hence, this new search model threatens the advertising revenue of content publishers, which depends on users actually visiting their website – and not just reading AI summaries of it.

To grasp the extraordinary significance of this case, particularly as Large Language Models (LLMs) increasingly generate search summaries, we need to look at the three main issues at the intersection of AI and existing copyright law: model training, the model itself, and the model’s output.

First, training an AI model on copyrighted content usually requires copying that content into a data set, formatting it, and processing it during the training and testing procedure. Like Company claims that Google used its protected content for training without a licence. Generally, this is illegal unless a specific copyright exemption applies that allows such training. In the US, such activities might fall under the general fair use defense, as two lower courts have ruled. In the EU, by contrast, a specific legal framework exists: the text and data mining (TDM) exceptions in the Copyright in the Digital Single Market (CDSM) Directive. However, there is ongoing debate whether these exceptions apply to the training of generative AI models at all. The CJEU will now have to decide this debate, and with it the fate of advanced AI training in the EU.

Second, once the model has been trained, another question arises: does the model itself qualify as a potentially illegal “copy” of the protected training material under copyright law? While AI models currently do not store images or text like a computer hard drive, they can reproduce exact training content when prompted. A phenomenon known as memorisation and model inversion attacks. Some scholars reasonably argue that the model itself may qualify as a copy under copyright law. The CJEU will, however, likely be able to bracket this tricky question.

Finally, the model’s output may resemble copyrighted works. This is particularly likely if the model was trained on copyrighted material. In such cases, the output itself may (again) violate copyright.

Overall, the CJEU case focuses on two of these issues: the use of copyrighted material for AI training, and the copyright status of AI-generated output.

Against this background, the CJEU has a chance to clarify the TDM framework in the EU and its application to AI. Hence, the case’s relevance goes well beyond the dispute between Like Company, the Hungarian press publisher, and Google about an unauthorised summary of a dolphin-relocation-related article.

The CJEU has been asked by the referring court (Budapest Környéki Törvényszék) to answer four questions. Two of the questions directly concern AI training. The other two questions address the output of the LLM. The CJEU must decide whether output that partially replicates protected press content, qualifies as reproduction or communication to the public, considering the probabilistic nature of AI content generation. It must also assess whether the TDM exception applies even in the absence of a license.

More specifically, Article 15 of the CDSM Directive introduces a new related right for press publishers to protect their online publications. This right gives them control over the digital use of their press content by information society service providers, particularly on platforms, such as Google or its Gemini chatbot. It covers reproduction and communication to the public of press publications or parts thereof. However, Google and other service providers remain free to use individual words or very short extracts without a license or exemption. The core issue, then, is how this right applies to summaries by AI chatbots, in contrast to classical hyperlinks in search engines replies. This precisely reflects the major shift from traditional search engines to AI-generated overviews.

While I do not possess a crystal ball to predict the CJEU judgment, unfortunately, the following answers seem possible and well justified. We shall look at them in the order in which they come up in AI training.

One question (more precisely: Question 2 posed by the referring court) is whether training an LLM-based chatbot count as reproduction under Article 2 of Directive 2001/29 (the so-called InfoSoc Directive), given that training involves observing and matching linguistic patterns. My answer to this is: yes.

Article 2 of the InfoSoc Directive fully harmonises, and contains an autonomous concept of “reproduction”. It also covers partial and temporary copies. The CJEU held that even eleven words may qualify as a reproduction if they reflect originality (Infopaq case).

In my view, training an LLM on press articles typically constitutes reproduction under Article 2 InfoSoc Directive because it usually involves copying protected expression into the system’s memory for analysis, even if not stored permanently. The CJEU has confirmed that even temporary, partial, and digital reproductions, such as those on a USB stick, can fall under reproduction rights when they contain original content.

The fact that the training involves “observing and matching patterns,” mediated through Natural Language Processing (NLP), does not change this. Reproduction may take different formats, and the purpose is irrelevant (except for the exceptions). One might ask whether training that involves only NLP analysis – without making any type of digital copies – would still count as reproduction. Is the right to mine merely a right to read – similar to reading a book?

This, however, is the wrong question to ask. In LLM training, text is split up into tokens and represented as numbers (more specifically, as high-dimensional vectors). The model then uses this mathematical representation, to generate new text when prompted by a human user. Whether these technical and mathematical steps count as separate reproductions cannot be fully answered here. For this to happen, the content needs to be at least temporarily copied to be broken up into tokens and converted into numbers. That process which involves “observing and matching of patterns” essentially captures the economic value of the work. It allows the system to reproduce it. Therefore, LLM training usually processes training data in a way that counts as “reproduction” under copyright law.

The next question (Question 3 of the referring court) is whether such training falls under the exception in Article 4 CDSM Directive, which permits text and data mining (TDM) of lawfully accessible works. In my view, the answer is yes.

This clearly is the bombshell question. If the TDM exception does not apply to LLM/AI training, AI providers are in very deep copyright trouble.

Article 4 CDSM Directive allows reproductions for commercial text and data mining if the source content is lawfully accessible and not subject to a machine-readable reservation. Thus, if the publisher has not explicitly opted out, reproductions for AI training purposes fall under this exception – if, and only if, generative AI training qualifies as text and data mining in the sense of Art. 4. Again, this is contested in academia.

Art. 2(2) CDSM defines “text and data mining” as “any automated analytical technique aimed at analysing text and data in digital form in order to generate information which includes but is not limited to patterns, trends and correlations.” To me, it seems fairly clear that generative AI training clearly fits this definition. It is an automated analytical technique, it analyses text and data, and it does that to generate information (directly, encoded in the model’s mathematical framework and indirectly, by enabling specific output). This open definition does not limit mining to non-generative AI, though transformer models (born in 2017) likely were not specifically considered by the CDSM legislators. Yet, Recital 18 CDSM confirms that text and data mining can lead to the “development of new applications or technologies,” exemplified by generative AI. Art. 53(1)(c) and Recital 105 AI Act arguably also take this as a given.

Admittedly, one could read Art. 4 and 2(2) CDSM narrowly, since generative AI training is more extensive than traditional TDM, and its output may commercially compete with the copyrighted works. But, in my view, these valid concerns are better addressed through new policy tools, such as a new compensation scheme, as discussed below. Ultimately, they do not speak against the applicability of the TDM exception to generative AI training.

The next question, captured in Question 1 of the referring court, concerns the output generated by an LLM-based chatbot. Specifically, the question is whether a chatbot’s response that includes text partially identical to protected press content and exceeds the “very short extract” threshold under Article 15 CDSM Directive qualifies as a communication to the public. This assessment must be made under both that directive and Article 3(2) of the InfoSoc Directive. Further, does the generative nature of the chatbot’s output, merely predicting the next word based on observed patterns, affect that classification?

My answer is, again, yes to the first, but no to the second subquestion.

Art. 15(1) CDSM grants press publishers rights to reproduction and communication to the public by referring to Art. 2 and 3(2) InfoSoc Directive. According to the definition, there needs to be 1) communication to 2) a public, and the public must be able to access the work 3) when and from where they want. The CJEU has clarified that giving access generally counts as communication; and that the public is “an indeterminate number of potential recipients […] involving a fairly large number of people.” Also, 4), a “new public” must be addressed, either through a different technical way than before or to a different audience.

In my view, a chatbot that displays protected press content qualifies as a communication to the public under Article 15(1) DSM and Article 3(2) InfoSoc Directive. It makes the content available to an indeterminate public – anyone using the AI system at a time and place of their choosing. The non-deterministic nature of AI output may differ from what the user expects. Sometimes it reproduces a work only after several prompts – or not at all. But the fact that generative AI is less reliable than other means of getting information (e.g., traditional search or databases) does not exempt it from copyright law. The chatbot also generates and delivers the content through a new technical means, which satisfies the CJEU’s “new public” criterion. The probabilistic and predictive nature of AI output is not decisive. Under EU law, what matters is the effect of the act, not the method used (with the only exception being the specific requirement of a “new technical means,” which is fulfilled here).

The final question (Question 4 of the referring court) asks whether Article 15(1) CDSM Directive and Article 2 InfoSoc Directive imply that when a user asks an LLM-based chatbot using wording that matches or refers to a press publication, and the chatbot responds by showing part or all of that publication’s content, this reproduction counts as attributable to the chatbot service provider. Again, my answer is yes.

When a chatbot reproduces part or all of a press article in response to a user prompt, the reproduction is attributable to the service provider, not (only) the user. It is the provider’s system that fixes and delivers protected content. Whether it fetches the material externally or generates it internally, this act triggers the reproduction right under Article 15(1) DSM and Article 2 InfoSoc Directive. Even making user-generated content available, without any content generated by a platform itself, can constitute a communication to the public. Importantly, no applicable exception justifies AI output when it exceeds a very short extract; the TDM exception itself does not cover the output.

This legal result presents a vexing policy problem. Unlike older forms of TDM, generative AI output may, in certain contexts, economically substitute the works it was trained on – for example in Internet search concerning news. If the Court confirms the above reasoning, the TDM exception would apply to AI training. However, content creators would not receive any remuneration unless it is specifically agreed by contract. Thus, EU policymakers arguably face the task of recalibrating the TDM framework in the upcoming revision of the CDSM Directive. A review process is already on its way.

Several policy options are available. One option would be to reverse the current default by introducing a necessary opt-in mechanism under Article 4 CDSM for commercial AI, requiring express rightsholder consent for TDM instead of permitting TDM unless expressly reserved.

Alternatively, the exception could be refined to differentiate between types of commercial uses, requiring opt-in only for general-purpose AI or certain applications (such as AI for entertainment), while retaining the opt-out format for particularly socially valuable contexts, such as commercial medical AI systems.

The third and, in my opinion, most attractive option is a clearly defined and administrable remuneration mechanism. It could work either through a statutory royalty scheme or a lump-sum levy paid to collective management organizations, based on verifiable parameters such as the type of output or the commercial availability of the resulting AI system. Otherwise, artists and creators may indeed be left behind. The future of search, and creative remuneration, depends on these policy choices, for better or worse.

The post Copyright, AI, and the Future of Internet Search before the CJEU appeared first on Verfassungsblog.

On July 3, 2025, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACtHR) issued Advisory Opinion AO-32/25, its most wide-ranging and ambitious interpretation of State obligations in the context of the climate emergency to date. The opinion responds to a request submitted by Colombia and Chile, and is notable not only for its breadth, but also for its potential to reshape how international human rights law responds to the climate crisis.

This post focuses on one notable aspect of AO-32/25 that has not received attention in other commentary–the IACtHR’s engagement with gender issues. The questions posed to the IACtHR explicitly incorporated a gender lens, a feature still rarely seen in international environmental or climate litigation. Chile and Colombia asked, among other things, what measures should be adopted to ensure the protection of environmental and territorial defenders, “as well as women, Indigenous Peoples and Afro-descendant communities” in the context of climate change. Specific questions also highlighted the differentiated and intersectional impacts of climate harm, and called on the IACtHR to address “gender-based violence, discrimination,” and the guarantees needed to protect the work of women human rights defenders. Although the IACtHR ultimately reformulated the questions and removed explicit references to gender in several parts, it retained a broad reference in Question 3, which asks about “the scope of obligations to respect, guarantee, and adopt the necessary measures to ensure, without discrimination, … the rights of women … as well as other vulnerable population groups in the context of the climate emergency” (para. 28).

In a previous post analyzing the KlimaSeniorinnen v. Switzerland decision of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), we noted that the ECtHR missed the opportunity to engage with the legal implications of gender and age as intersecting determinants of climate vulnerability. Although the case centered on elderly women, and the ECtHR acknowledged scientific evidence showing their heightened vulnerability to climate-related harms, it ultimately sidelined gender as a legally relevant factor, treating it as part of the background rather than as a basis for rights and remedies. This reflects a broader gap in climate litigation, where gender—despite its centrality to lived experiences of climate harm—remains underexplored and legally underdeveloped.

As we turn to the IACtHR’s AO-32/25, we ask: has this gap begun to close? Does the IACtHR, with its jurisprudence on gender and diversity, offer a more robust framework for understanding and addressing gendered dimensions of climate change? We find that the IACtHR has indeed taken an important step forward, both in recognizing gender as a key determinant of climate vulnerability and in identifying gender-responsive obligations on States. However, the IACtHR’s comments in this regard remain general and often gestural. The obligations identified are limited, narrow, and many relate to data gathering rather than substantial action. Thus, while AO-32/25 is a clear advance in addressing gender in climate litigation, it also reveals the extent of the work that remains to be done.

In AO-32/25, the IACtHR makes several important findings regarding gender and the rights of women in the context of the climate crisis.

Disproportionate Impact on Women

The IACtHR acknowledges that climate change has a disproportionate impact on women, particularly those living in poverty, rural areas, or communities that heavily rely on natural resources (para. 594). It emphasizes that climate impacts exacerbate existing gender inequalities, leading to heightened vulnerability in areas such as health, access to water, food security, and exposure to violence (para. 571). In the context of climate disasters, both sudden and slow onset, the IACtHR notes how women can be differentially affected, with women and girls being at greater risk of gender-based violence in the aftermath of disasters (para. 614). As primary breadwinners, caretakers of the family, and water collectors due to dominant understandings of gender roles, they are disproportionately affected by the impacts on food and water security, as well as the health of their household members (para. 420).

Intersectionality and Vulnerability

The IACtHR highlights the need for an intersectional approach that considers how overlapping factors—such as gender, race, Indigeneity, ethnicity, class, and age—shape exposure to climate harm (para. 592). It stresses that women, especially Indigenous and Afro-descendant women, face unique barriers to participation and access to justice, which States must actively address (para. 613). While intersectionality is embraced as a critical dimension of understanding risk and harm, the IACtHR, like other courts before it, takes very limited cognisance of gender as a critical concern in relation to certain other social demographics, specifically including being a child or young person. The discussion of the differentiated protection for children and adolescents, for example (para. 597-604), largely treats children as a universal category, undifferentiated by gender. The IACtHR merely mentions that gender is a relevant factor in the perception of impact with respect to the intersection of vulnerabilities, noting that girls and female adolescents are more vulnerable to climate impacts, deepening existing inequalities (para. 598, see here and here).

LGBTQ+ and Gender-Diverse Communities

Significantly, the IACtHR recognizes the heightened vulnerability of gender diverse persons during and after climate-induced disasters, who face a greater risk of gender-based violence due to stigmatisation and discrimination (para. 618). In discussing the need for adaptation measures, the IACtHR underscores that when evaluating climate impacts, vulnerability, and risk, States must rely on exhaustive data and identify the rights and groups of people that are particularly vulnerable, including women, girls, and the LGBTIQ+ community (para. 389). However, the Court does not provide further detail on the differentiated impacts suffered by this community in the context of the climate crisis, nor does it specify what kind of data supports adaptation plans. This is particularly important since data collection regarding impacts on LGBTIQ+ and gender-diverse communities in the aftermath of disasters is often overlooked and neglected (see here).

Women Environmental Defenders

The opinion also addresses the situation of women environmental defenders (para. 571-572), affirming that States must take special measures to protect them from threats, violence, and reprisals (para. 566). The Court calls attention to the gendered nature of violence and persecution faced by these defenders and links their protection to the obligations under both the American Convention and the Escazú Agreement (para. 564).

The IACtHR finds that States have heightened and specific obligations to ensure the substantive and procedural rights of those whose intersecting identities make them more vulnerable to discrimination and harm, including their gender identities. Most of these obligations are overly general and normatively thin; where they are more detailed, they relate to gathering information that is gender-representative and sensitive, including the duty to consult and involve women meaningfully in climate decision-making, and guarantee access to justice and effective remedies for gender-differentiated harms.

The IACtHR expands on the content of the right to access to information, which imposes on states the obligation to establish systems and mechanisms to produce, compile, analyse, and disseminate information relevant to the protection of human rights in the context of the climate emergency (para. 505). According to the IACtHR, states must: (1) collect data (in relation to environmental impact assessments) on the effects of climate change on vulnerable individuals and groups, including the dimensions of gender (para. 496), (2) have a system of indicators to measure progress in implementing state strategies to move towards sustainable development that includes statistics on gender, among other factors that cause and deepen inequality in the context of the climate emergency (para. 508), and (3) collect, systematize, produce and analyze information on current and projected impacts of climate change (in the context of adaptation and disaster risk management) on people’s lives, personal integrity and health, considering gender (para. 512).

With respect to environmental and human rights defenders, the IACtHR notes that States must collect and keep updated data on killings, abductions, enforced disappearances, arbitrary detentions, torture, and other harmful acts against environmental defenders, considering gender as a relevant and differentiating factor (para. 575). The IACtHR underscores that women defenders are faced with gender stereotypes that aim to delegitimize their work (para. 572). Furthermore, the IACtHR highlights the specific risks that women face due to the intersection of multiple axes of oppression (para. 572). Hence, the Court calls on States to include domestic mechanisms specifically designed to protect women defenders, as well as rural, Afro-descendant, and Indigenous women (para. 577).

Regarding gender-diverse individuals, the IACtHR identifies specific obligations, but these are primarily concerned with health and disaster response. The Court finds that States have an obligation to: “(i) ensure that LGBTIQ+ persons have access to health care free from discrimination by ensuring that health care personnel in these situations have the necessary diversity and inclusion training; and (ii) encourage the creation of safe spaces to prevent and effectively address any acts of discrimination and harassment of LGBTIQ+ persons in temporary shelters. Similarly, States have an obligation to ensure that health care provided to LGBTIQ+ persons during and after climate change-induced disasters is available, accessible, acceptable and of good quality.” (para 618).

With respect to Indigenous and tribal communities, the IACtHR discusses the obligations to adopt a series of progressive measures to design and implement studies, registers, and statistical reports to obtain data on the impacts of climate change on access to their territories and means necessary to their subsistence, noting that they should include intersectional factors related to “gender, age, and disability self-identification.” (para. 606). The IACtHR recognizes explicitly the role of Indigenous women in the preservation and transmission of traditional knowledge, including their contributions to maintaining cultural identity, mitigating the risks and effects of climate change, protecting biodiversity, achieving sustainable development, and building resilience to extreme events.

Furthermore, the IACtHR stipulates that States must design and implement mitigation, adaptation, and reparation measures that are gender-responsive, ensuring that climate action promotes gender equality and does not reinforce structural discrimination.

In sum, the IACtHR establishes that the climate crisis is a gendered human rights issue and that States have affirmative duties to integrate gender equality into their climate responses, protect women’s rights, and remedy climate-related harms experienced by women and girls. It underscores that a gender and intersectional perspective should inform all actions undertaken in the context of the climate emergency (para. 614).

However, while these acknowledgments are important symbolically and represent a step forward compared to previous jurisprudence, the IACtHR’s treatment of gender remains overly general and normatively thin. The language used is wide-ranging and aspirational, but it lacks concrete guidance on what the affirmative duties involve in practice. For instance, AO-32/25 does not clarify the legal consequences for States that fail to adopt a gender-transformative climate policy, nor does it outline concrete steps for ensuring gender-responsive adaptation, mitigation, or access to remedies. The reference to intersectionality is notable, but the Court stops short of explaining how overlapping identities—such as indigeneity, poverty, or displacement—should shape legal obligations or institutional reforms.

Ultimately, while the IACtHR affirms the need for a gender perspective, its reasoning falls short of establishing meaningful obligations that would help translate that recognition into enforceable protections. In this respect, AO-32/25 marks progress, but not transformation—a symbolic step in the right direction, but one that leaves much of the substantive work to future litigation or state interpretation.

To fully appreciate the significance of AO-32/25 on gender issues, it should be read in conjunction with the IACtHR’s prior advisory opinions on gender identity, equality, and diversity. Unlike other international courts, the IACtHR has developed a relatively rich and evolving approach to gender, notably through Advisory Opinion 24/17 (AO-24/17), which recognized gender identity and same-sex relationships as protected under the American Convention (see here). When these opinions are read together, a more nuanced understanding of gendered state obligations in the context of climate change emerges—one that goes beyond vulnerability tropes to acknowledge intersectionality, agency, and structural inequality.

AO-24/17 was, in critical respects, quite narrow. In relation to gender-diverse persons and transgender rights, the advisory opinion focused primarily on state obligations to recognise and facilitate name changes in accordance with gender identity. However, despite the fairly narrow scope of the questions posed by Costa Rica in requesting the opinion, the IACtHR recognised the broad discrimination and oppression that gender diverse and LGBTIQ+ persons face, and the fact that this discrimination is often State-mandated and specifically provided for in law. It also recognised that transgender persons face constraints and rights violations across every aspect of their lives, including in accessing housing, employment, health care, and contractual obligations, among others. Given this, in AO-24/17, the IACtHR emphasized the importance of identity recognition, including through enabling name change and other formal dimensions of recognition, as a crucial first step towards realizing the full human rights of trans and gender-diverse persons.

Whereas in AO-24/17 the IACtHR recognized that gender and gender-based discrimination permeate all aspects of an individual’s life—including family, education, work, health, political participation, and personal autonomy—the discussion of gender in AO-32/25 is noticeably narrower in scope and ambition. Although the IACtHR affirms that the climate crisis has differentiated impacts on women and girls and acknowledges the need for a gender and intersectional lens (para. 614), its analysis is largely confined to the domains of health and disaster response. This represents a significant contraction from the broader framing in AO-24/17, where gender was treated as a structural axis of inequality with far-reaching implications.

Moreover, while AO-32/25 does mention LGBTIQ+ persons, it does so primarily within the context of access to healthcare and vulnerability during emergencies (paras. 317, 616), without elaborating on the multiple and intersecting forms of exclusion they may face in areas such as housing, land rights, employment, or access to justice—domains where climate impacts are also acutely felt. As such, the IACtHR seems to adopt a binary approach to gender, except for a couple of paragraphs that mention the LGBTIQ+ and gender-diverse communities. A more holistic application of the reasoning from AO-24/17 would have required the IACtHR to engage more deeply with how climate change exacerbates existing gender-based inequalities across social, economic, and political spheres.

For instance, AO-32/25 could have addressed how climate-induced displacement disrupts education for girls, increases risks of gender-based violence, or undermines women’s rights to land, property, and participation in decision-making. By limiting its gender analysis to only a few sectors, the Court missed an opportunity to build on its prior jurisprudence and to articulate a truly comprehensive gender-responsive framework for climate governance.

The IACtHR’s AO-32/25 is groundbreaking. Acknowledging the gendered dimensions of the climate crisis is a crucial step in recognizing the differentiated ways in which climate change affects people and closing the gender gap. Notably, the intersectional approach adopted by the IACtHR sheds light on the particular adverse climate impacts experienced by certain groups and individuals, an aspect that has been largely ignored in the broader scheme of climate litigation. However, while AO-32/25 presents a more meaningful engagement with gender and its relation to climate change than, for example, the ECtHR in KlimaSeniorinnen, it still falls short when addressing gender beyond women and girls. Given the IACtHR’s previous treatment of gender-diverse peoples’ rights, this feels like a missed opportunity to expand further and critically assess the gendered impacts of climate change in the region.

The post A Nod, Not a Leap appeared first on Verfassungsblog.

:

Kann Feed nicht laden oder parsen

cURL error 22: The requested URL returned error: 403

:

Kann Feed nicht laden oder parsen

cURL error 28: Connection timed out after 10006 milliseconds

Feed Titel: Wissenschaft - News und Hintergründe zu Wissen & Forschung | NZZ

Feed Titel: Vera Lengsfeld

Feed Titel: Verfassungsblog

Writing in Verfassungsblog in April 2024, shortly after the European Court of Human Rights’ (ECtHR) landmark climate judgment in KlimaSeniorinnen, Chris Hilson argued that the ‘most ambiguous and potentially contentious part of the ruling relates to the Court’s discussion of “carbon budgets” (paras. 550, 569-573).’

The context was the Court’s interpretation of the margin of appreciation – the level of deference the ECtHR will grant to a State – in the context of climate change. Here, the Court drew a distinction between the reduced margin of appreciation for States when setting ‘the requisite aims and objectives’ in respect of the State’s commitment to the necessity of combating climate change and its adverse effects, and the wide margin of appreciation States have in choosing the means designed to achieve those objectives (para. 543).

While describing the point as ‘ambiguous’, Professor Hilson ultimately concluded that ‘the [ECtHR] associates the issue of [carbon] budget setting with a wide margin of appreciation’. The purpose of the present contribution is to put the alternative view. Namely, that the setting of a particular national carbon budget represents the setting of ‘the requisite aims and objectives’ to combat climate change and its adverse effects, to which a reduced margin of appreciation applies, rather than simply being ‘the choice of means designed to achieve those objectives,’ where a wide margin of appreciation would apply (para. 543).

Professor Hilson’s analysis is based on carbon budgets being ‘used in two senses in the climate law and policy world.’ In the first sense, ‘they can, like the United Kingdom’s carbon budgets simply lay out a cap or maximum level that GHG emissions must be brought below in order to meet the climate targets that a state has set.’ In the second sense, the remaining global carbon budget associated with a particular global average temperature increase – 1.5°C, say – is calculated and then ‘divided up between states, in line with “fair shares.”’

In other words, under Professor Hilson’s analysis, a national climate target sets the aim or objective, with the national carbon budget simply laying out a cap or maximum level that greenhouse gas emissions must be brought below in order to meet the climate targets that a state has set. In our view, the relationship between climate targets and carbon budgets is such that the latter are never simply instrumental; rather, they always represent a choice between different aims and objectives.

To explain: a national climate target is typically a point-to-point comparison based on annual emissions in a country in two particular years: a baseline year and the target year. For example, in Ireland, the Climate Change Advisory Council was instructed by section 6A(5) of Ireland’s Climate Act to propose carbon budgets ‘such that the total amount of annual greenhouse gas emissions in the year ending on 31 December 2030 is 51 per cent less than the annual greenhouse gas emissions reported for the year ending on 31 December 2018’.

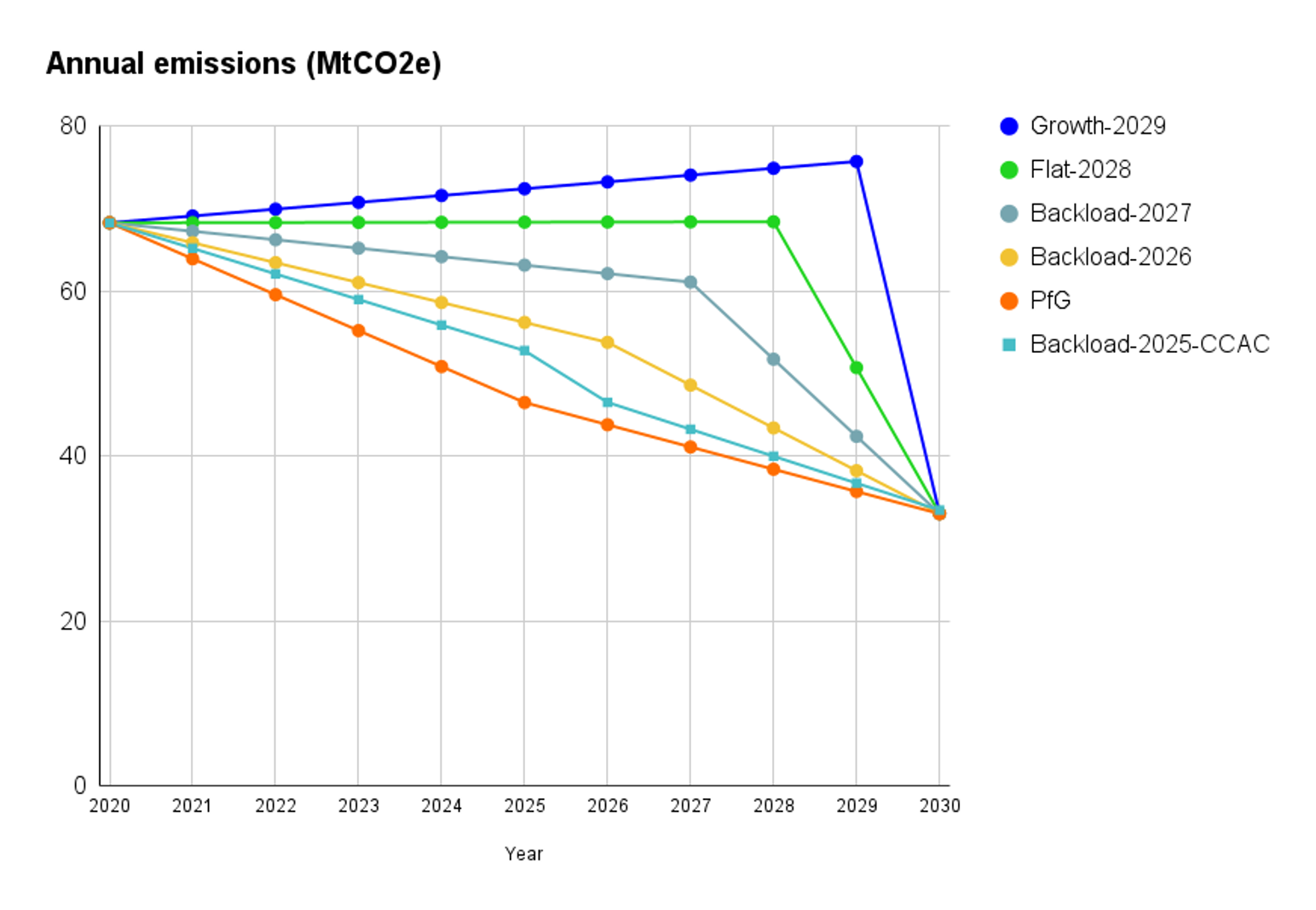

However, this instruction did not meaningfully constrain the carbon budgets that could be proposed and adopted, because there are lots of different pathways between Ireland’s annual emissions in 2018 and its annual emissions that are 51% below this in 2030, and each of these pathways has a different carbon budget associated with it. This is well illustrated by the Figure below: the carbon budget associated with each pathway (the area ‘under the line’ in each case) varies wildly.

Figure: Indicative emissions reduction pathways that are all notionally consistent with s.6A(5) of Ireland’s Climate Act (figure produced by Professor Barry McMullin).

In other words, a climate target sets the framework; it indicates what a country’s annual emissions are to be in a single year at the end of the period; it therefore sets an aim or objective in that sense, and ought to be subject to a reduced margin of appreciation per KlimaSeniorinnen. In turn, a carbon budget adopted within this framework also sets an aim or objective in KlimaSeniorinnen terms, because it is the budget that constrains the country’s contribution to climate change on a multi-annual basis. (Importantly, both targets and carbon budgets (or an equivalent method of quantification) are required by the KlimaSeniorinnen judgment: para. 550(a) and (b).)

A numerical climate target admits of and is equivocal between lots of different carbon budgets, each of which results in a different national contribution to global temperature increase. To put the point another way, the difference is between simply being given two points on a graph (the target, which compares annual emissions in two individual years) and being given the pathway that joins those two points (from which the budget can be calculated, constraining emissions for all years between the two points on the graph).

Since climate change is a problem of cumulative emissions since the beginning of the industrial revolution (Fig SPM.10 on p.18), carbon budgets are capable of constraining temperature increase in line with the Paris Agreement’s temperature goals, while climate targets alone are not. Further, in terms of the internal coherence of the KlimaSeniorinnen judgment, the alternative view, allowing States a wide margin of appreciation in the setting of national carbon budgets, would not be an approach to the ECHR that would ‘guarantee rights that are practical and effective’ (para. 545).

Thus, in our view, ‘the choice of means designed to achieve [a State’s climate] objectives’ (para. 543), to which a wide margin of appreciation applies, does not encompass the setting of carbon budgets, but rather captures policy choices such as which policies to adopt to decarbonise the energy system, how to reduce agricultural emissions, how to reduce emissions from transport, etc: these are the ‘operational choices and policies adopted in order to meet internationally anchored targets and commitments in the light of priorities and resources,’ of which the ECtHR speaks in its judgment in the context of a wide margin of appreciation (at para. 543).

It has been strongly argued by Dennis van Berkel et al in a recent contribution that, falling within the reduced margin of appreciation, KlimaSeniorinnen requires States to quantify a national fair share carbon budget that is set in relation to the remaining global carbon budget to limit heating to 1.5°C. In finding a breach of Article 8 ECHR in KlimaSeniorinnen, the ECtHR applied a quantification of a Swiss fair share carbon budget for 1.5°C (at para. 569), and rejected the argument put forward by Switzerland that its ‘national climate policy [which established targets] could be considered as being similar in approach to establishing a carbon budget’ (at paras. 570 and 360). As van Berkel et al note, ‘only a national carbon budget that is set in relation to the remaining global budget can be capable of mitigating the consequences of climate change, and thus practically and effectively protect human rights’ (cf. para. 545 of KlimaSeniorinnen). Notably, the Norwegian and Dutch National Human Rights Institutes have reached the same conclusion, as highlighted by a coalition of NGOs in their submission to the Committee of Ministers as part of the ongoing supervision of the implementation of the KlimaSeniorinnen judgment.

This obligation to quantify each country’s fair share of the remaining global budget to limit heating to 1.5°C will remain vital even as countries’ fair shares are used up (as will soon be the case for the European Union, for example, even on the ‘most lenient’ interpretation of fair share). This quantification will represent a line in the sand at a particular moment in time, calculated with reference to a particular baseline year. This will enable States to be held accountable, insofar as is possible, for their ‘carbon debt’, once their quantified fair share has run out. This seems likely to represent a new frontier in climate litigation in the not-too-distant future.

It must be recognised, however, that there are feasibility and sustainability concerns in terms of the amount of carbon debt that can be ‘repaid’ by way of net negative emissions, such that States’ primary focus should remain on rapid and deep reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. Further, the global average temperature decline as a result of net negative emissions (if achievable) is projected to be sluggish, and certain impacts will continue for many years. As the IPCC explains, ‘[i]f global net negative CO2 emissions were to be achieved and be sustained, the global CO2-induced surface temperature increase would be gradually reversed but other climate changes would continue in their current direction for decades to millennia (high confidence). For instance, it would take several centuries to millennia for global mean sea level to reverse course even under large net negative CO2 emissions.’

‘Gradually’ is the key word when it comes to reversing global temperatures: as Climate Analytics explains, ‘even under optimistic assumptions related to CDR [carbon dioxide removal] deployment and effectiveness, only about 0.05°C of global mean temperature increase may be reversible per decade.’

Barry McMullin et al thus argue that adopting a carbon debt framing ‘may help facilitate early nation-level societal discussion of whether, or how much, CO2 debt can or should be taken on, and the interaction of this with alternative pathways for earlier, deeper, mitigation of gross emissions which would allow that ultimate debt to be reduced or avoided altogether’. They conclude, ‘if large scale removal services prove difficult or infeasible to scale up, then this should prompt earlier and more severe limitation on the accumulation of CO2 debt.’

An obligation to quantify each country’s fair share of the remaining global carbon budget associated with limiting global heating to 1.5°C flows from the judgment in KlimaSeniorinnen. While there will naturally be debate about what represents a country’s fair share – the EU’s independent advisory body ESAB recently considered a range of fair share principles and concluded that the EU’s fair share has already been used up under many of these – the obligation to quantify fair share budgets should, in our view, be the subject of a reduced margin of appreciation consistent with KlimaSeniorinnen.

The post Quantifying Fair Share Carbon Budgets appeared first on Verfassungsblog.

It is a busy time in AI and copyright law. Alongside a growing body of academic analysis and media coverage, real-world litigation, possible regulatory measures, and first lower court rulings are now beginning to shape the field.

With Like Company v Google, the first groundbreaking AI copyright case is now headed to the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). In this case, a Hungarian press publisher challenges Google and its Gemini chatbot for reproducing and communicating its editorial content without authorisation.

The Court’s decision will establish the legal framework for AI’s relationship with copyright and press publishers’ rights across the EU. It will potentially reshape how generative AI systems can or cannot lawfully access, process and reproduce journalistic and other protected content. This may even fundamentally affect the economic and technical architecture of future AI development.

In this piece, I will not only try to answer the questions the CJEU will have to grapple with. I also argue that the legally correct answers expose a very serious policy problem: namely, the lack of coherent mechanisms to ensure appropriate remuneration for rightsholders. A problem that requires immediate attention by European legislators.

In Like Company v Google, a Hungarian press publisher sued Google Ireland after its Gemini chatbot generated a detailed summary of one of its articles. That piece described a celebrity’s plan to introduce dolphins to Lake Balaton; when prompted by a user, Gemini reproduced substantial portions of the protected content. The Budapest court referred four questions to the CJEU to determine whether such AI-generated responses constitute copyright infringement through unauthorized reproduction and communication to the public under EU copyright directives.

This case is not only the first case at the intersection of AI and copyright to reach the CJEU. It also reflects a broader shift that could reshape much of the information ecosystem. Generative AI is now built into search engines like Google, Bing, or ChatGPT Search and Perplexity. Instead of showing lists of websites, they increasingly offer direct answers or summaries. This redirects user traffic. Instead of clicking on links, users may increasingly only read the AI-generated summaries. Hence, this new search model threatens the advertising revenue of content publishers, which depends on users actually visiting their website – and not just reading AI summaries of it.

To grasp the extraordinary significance of this case, particularly as Large Language Models (LLMs) increasingly generate search summaries, we need to look at the three main issues at the intersection of AI and existing copyright law: model training, the model itself, and the model’s output.

First, training an AI model on copyrighted content usually requires copying that content into a data set, formatting it, and processing it during the training and testing procedure. Like Company claims that Google used its protected content for training without a licence. Generally, this is illegal unless a specific copyright exemption applies that allows such training. In the US, such activities might fall under the general fair use defense, as two lower courts have ruled. In the EU, by contrast, a specific legal framework exists: the text and data mining (TDM) exceptions in the Copyright in the Digital Single Market (CDSM) Directive. However, there is ongoing debate whether these exceptions apply to the training of generative AI models at all. The CJEU will now have to decide this debate, and with it the fate of advanced AI training in the EU.

Second, once the model has been trained, another question arises: does the model itself qualify as a potentially illegal “copy” of the protected training material under copyright law? While AI models currently do not store images or text like a computer hard drive, they can reproduce exact training content when prompted. A phenomenon known as memorisation and model inversion attacks. Some scholars reasonably argue that the model itself may qualify as a copy under copyright law. The CJEU will, however, likely be able to bracket this tricky question.

Finally, the model’s output may resemble copyrighted works. This is particularly likely if the model was trained on copyrighted material. In such cases, the output itself may (again) violate copyright.

Overall, the CJEU case focuses on two of these issues: the use of copyrighted material for AI training, and the copyright status of AI-generated output.

Against this background, the CJEU has a chance to clarify the TDM framework in the EU and its application to AI. Hence, the case’s relevance goes well beyond the dispute between Like Company, the Hungarian press publisher, and Google about an unauthorised summary of a dolphin-relocation-related article.

The CJEU has been asked by the referring court (Budapest Környéki Törvényszék) to answer four questions. Two of the questions directly concern AI training. The other two questions address the output of the LLM. The CJEU must decide whether output that partially replicates protected press content, qualifies as reproduction or communication to the public, considering the probabilistic nature of AI content generation. It must also assess whether the TDM exception applies even in the absence of a license.

More specifically, Article 15 of the CDSM Directive introduces a new related right for press publishers to protect their online publications. This right gives them control over the digital use of their press content by information society service providers, particularly on platforms, such as Google or its Gemini chatbot. It covers reproduction and communication to the public of press publications or parts thereof. However, Google and other service providers remain free to use individual words or very short extracts without a license or exemption. The core issue, then, is how this right applies to summaries by AI chatbots, in contrast to classical hyperlinks in search engines replies. This precisely reflects the major shift from traditional search engines to AI-generated overviews.

While I do not possess a crystal ball to predict the CJEU judgment, unfortunately, the following answers seem possible and well justified. We shall look at them in the order in which they come up in AI training.

One question (more precisely: Question 2 posed by the referring court) is whether training an LLM-based chatbot count as reproduction under Article 2 of Directive 2001/29 (the so-called InfoSoc Directive), given that training involves observing and matching linguistic patterns. My answer to this is: yes.

Article 2 of the InfoSoc Directive fully harmonises, and contains an autonomous concept of “reproduction”. It also covers partial and temporary copies. The CJEU held that even eleven words may qualify as a reproduction if they reflect originality (Infopaq case).

In my view, training an LLM on press articles typically constitutes reproduction under Article 2 InfoSoc Directive because it usually involves copying protected expression into the system’s memory for analysis, even if not stored permanently. The CJEU has confirmed that even temporary, partial, and digital reproductions, such as those on a USB stick, can fall under reproduction rights when they contain original content.

The fact that the training involves “observing and matching patterns,” mediated through Natural Language Processing (NLP), does not change this. Reproduction may take different formats, and the purpose is irrelevant (except for the exceptions). One might ask whether training that involves only NLP analysis – without making any type of digital copies – would still count as reproduction. Is the right to mine merely a right to read – similar to reading a book?

This, however, is the wrong question to ask. In LLM training, text is split up into tokens and represented as numbers (more specifically, as high-dimensional vectors). The model then uses this mathematical representation, to generate new text when prompted by a human user. Whether these technical and mathematical steps count as separate reproductions cannot be fully answered here. For this to happen, the content needs to be at least temporarily copied to be broken up into tokens and converted into numbers. That process which involves “observing and matching of patterns” essentially captures the economic value of the work. It allows the system to reproduce it. Therefore, LLM training usually processes training data in a way that counts as “reproduction” under copyright law.

The next question (Question 3 of the referring court) is whether such training falls under the exception in Article 4 CDSM Directive, which permits text and data mining (TDM) of lawfully accessible works. In my view, the answer is yes.

This clearly is the bombshell question. If the TDM exception does not apply to LLM/AI training, AI providers are in very deep copyright trouble.

Article 4 CDSM Directive allows reproductions for commercial text and data mining if the source content is lawfully accessible and not subject to a machine-readable reservation. Thus, if the publisher has not explicitly opted out, reproductions for AI training purposes fall under this exception – if, and only if, generative AI training qualifies as text and data mining in the sense of Art. 4. Again, this is contested in academia.

Art. 2(2) CDSM defines “text and data mining” as “any automated analytical technique aimed at analysing text and data in digital form in order to generate information which includes but is not limited to patterns, trends and correlations.” To me, it seems fairly clear that generative AI training clearly fits this definition. It is an automated analytical technique, it analyses text and data, and it does that to generate information (directly, encoded in the model’s mathematical framework and indirectly, by enabling specific output). This open definition does not limit mining to non-generative AI, though transformer models (born in 2017) likely were not specifically considered by the CDSM legislators. Yet, Recital 18 CDSM confirms that text and data mining can lead to the “development of new applications or technologies,” exemplified by generative AI. Art. 53(1)(c) and Recital 105 AI Act arguably also take this as a given.

Admittedly, one could read Art. 4 and 2(2) CDSM narrowly, since generative AI training is more extensive than traditional TDM, and its output may commercially compete with the copyrighted works. But, in my view, these valid concerns are better addressed through new policy tools, such as a new compensation scheme, as discussed below. Ultimately, they do not speak against the applicability of the TDM exception to generative AI training.

The next question, captured in Question 1 of the referring court, concerns the output generated by an LLM-based chatbot. Specifically, the question is whether a chatbot’s response that includes text partially identical to protected press content and exceeds the “very short extract” threshold under Article 15 CDSM Directive qualifies as a communication to the public. This assessment must be made under both that directive and Article 3(2) of the InfoSoc Directive. Further, does the generative nature of the chatbot’s output, merely predicting the next word based on observed patterns, affect that classification?

My answer is, again, yes to the first, but no to the second subquestion.

Art. 15(1) CDSM grants press publishers rights to reproduction and communication to the public by referring to Art. 2 and 3(2) InfoSoc Directive. According to the definition, there needs to be 1) communication to 2) a public, and the public must be able to access the work 3) when and from where they want. The CJEU has clarified that giving access generally counts as communication; and that the public is “an indeterminate number of potential recipients […] involving a fairly large number of people.” Also, 4), a “new public” must be addressed, either through a different technical way than before or to a different audience.

In my view, a chatbot that displays protected press content qualifies as a communication to the public under Article 15(1) DSM and Article 3(2) InfoSoc Directive. It makes the content available to an indeterminate public – anyone using the AI system at a time and place of their choosing. The non-deterministic nature of AI output may differ from what the user expects. Sometimes it reproduces a work only after several prompts – or not at all. But the fact that generative AI is less reliable than other means of getting information (e.g., traditional search or databases) does not exempt it from copyright law. The chatbot also generates and delivers the content through a new technical means, which satisfies the CJEU’s “new public” criterion. The probabilistic and predictive nature of AI output is not decisive. Under EU law, what matters is the effect of the act, not the method used (with the only exception being the specific requirement of a “new technical means,” which is fulfilled here).

The final question (Question 4 of the referring court) asks whether Article 15(1) CDSM Directive and Article 2 InfoSoc Directive imply that when a user asks an LLM-based chatbot using wording that matches or refers to a press publication, and the chatbot responds by showing part or all of that publication’s content, this reproduction counts as attributable to the chatbot service provider. Again, my answer is yes.

When a chatbot reproduces part or all of a press article in response to a user prompt, the reproduction is attributable to the service provider, not (only) the user. It is the provider’s system that fixes and delivers protected content. Whether it fetches the material externally or generates it internally, this act triggers the reproduction right under Article 15(1) DSM and Article 2 InfoSoc Directive. Even making user-generated content available, without any content generated by a platform itself, can constitute a communication to the public. Importantly, no applicable exception justifies AI output when it exceeds a very short extract; the TDM exception itself does not cover the output.

This legal result presents a vexing policy problem. Unlike older forms of TDM, generative AI output may, in certain contexts, economically substitute the works it was trained on – for example in Internet search concerning news. If the Court confirms the above reasoning, the TDM exception would apply to AI training. However, content creators would not receive any remuneration unless it is specifically agreed by contract. Thus, EU policymakers arguably face the task of recalibrating the TDM framework in the upcoming revision of the CDSM Directive. A review process is already on its way.

Several policy options are available. One option would be to reverse the current default by introducing a necessary opt-in mechanism under Article 4 CDSM for commercial AI, requiring express rightsholder consent for TDM instead of permitting TDM unless expressly reserved.

Alternatively, the exception could be refined to differentiate between types of commercial uses, requiring opt-in only for general-purpose AI or certain applications (such as AI for entertainment), while retaining the opt-out format for particularly socially valuable contexts, such as commercial medical AI systems.

The third and, in my opinion, most attractive option is a clearly defined and administrable remuneration mechanism. It could work either through a statutory royalty scheme or a lump-sum levy paid to collective management organizations, based on verifiable parameters such as the type of output or the commercial availability of the resulting AI system. Otherwise, artists and creators may indeed be left behind. The future of search, and creative remuneration, depends on these policy choices, for better or worse.

The post Copyright, AI, and the Future of Internet Search before the CJEU appeared first on Verfassungsblog.

On July 3, 2025, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACtHR) issued Advisory Opinion AO-32/25, its most wide-ranging and ambitious interpretation of State obligations in the context of the climate emergency to date. The opinion responds to a request submitted by Colombia and Chile, and is notable not only for its breadth, but also for its potential to reshape how international human rights law responds to the climate crisis.

This post focuses on one notable aspect of AO-32/25 that has not received attention in other commentary–the IACtHR’s engagement with gender issues. The questions posed to the IACtHR explicitly incorporated a gender lens, a feature still rarely seen in international environmental or climate litigation. Chile and Colombia asked, among other things, what measures should be adopted to ensure the protection of environmental and territorial defenders, “as well as women, Indigenous Peoples and Afro-descendant communities” in the context of climate change. Specific questions also highlighted the differentiated and intersectional impacts of climate harm, and called on the IACtHR to address “gender-based violence, discrimination,” and the guarantees needed to protect the work of women human rights defenders. Although the IACtHR ultimately reformulated the questions and removed explicit references to gender in several parts, it retained a broad reference in Question 3, which asks about “the scope of obligations to respect, guarantee, and adopt the necessary measures to ensure, without discrimination, … the rights of women … as well as other vulnerable population groups in the context of the climate emergency” (para. 28).

In a previous post analyzing the KlimaSeniorinnen v. Switzerland decision of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), we noted that the ECtHR missed the opportunity to engage with the legal implications of gender and age as intersecting determinants of climate vulnerability. Although the case centered on elderly women, and the ECtHR acknowledged scientific evidence showing their heightened vulnerability to climate-related harms, it ultimately sidelined gender as a legally relevant factor, treating it as part of the background rather than as a basis for rights and remedies. This reflects a broader gap in climate litigation, where gender—despite its centrality to lived experiences of climate harm—remains underexplored and legally underdeveloped.

As we turn to the IACtHR’s AO-32/25, we ask: has this gap begun to close? Does the IACtHR, with its jurisprudence on gender and diversity, offer a more robust framework for understanding and addressing gendered dimensions of climate change? We find that the IACtHR has indeed taken an important step forward, both in recognizing gender as a key determinant of climate vulnerability and in identifying gender-responsive obligations on States. However, the IACtHR’s comments in this regard remain general and often gestural. The obligations identified are limited, narrow, and many relate to data gathering rather than substantial action. Thus, while AO-32/25 is a clear advance in addressing gender in climate litigation, it also reveals the extent of the work that remains to be done.

In AO-32/25, the IACtHR makes several important findings regarding gender and the rights of women in the context of the climate crisis.

Disproportionate Impact on Women

The IACtHR acknowledges that climate change has a disproportionate impact on women, particularly those living in poverty, rural areas, or communities that heavily rely on natural resources (para. 594). It emphasizes that climate impacts exacerbate existing gender inequalities, leading to heightened vulnerability in areas such as health, access to water, food security, and exposure to violence (para. 571). In the context of climate disasters, both sudden and slow onset, the IACtHR notes how women can be differentially affected, with women and girls being at greater risk of gender-based violence in the aftermath of disasters (para. 614). As primary breadwinners, caretakers of the family, and water collectors due to dominant understandings of gender roles, they are disproportionately affected by the impacts on food and water security, as well as the health of their household members (para. 420).

Intersectionality and Vulnerability

The IACtHR highlights the need for an intersectional approach that considers how overlapping factors—such as gender, race, Indigeneity, ethnicity, class, and age—shape exposure to climate harm (para. 592). It stresses that women, especially Indigenous and Afro-descendant women, face unique barriers to participation and access to justice, which States must actively address (para. 613). While intersectionality is embraced as a critical dimension of understanding risk and harm, the IACtHR, like other courts before it, takes very limited cognisance of gender as a critical concern in relation to certain other social demographics, specifically including being a child or young person. The discussion of the differentiated protection for children and adolescents, for example (para. 597-604), largely treats children as a universal category, undifferentiated by gender. The IACtHR merely mentions that gender is a relevant factor in the perception of impact with respect to the intersection of vulnerabilities, noting that girls and female adolescents are more vulnerable to climate impacts, deepening existing inequalities (para. 598, see here and here).

LGBTQ+ and Gender-Diverse Communities

Significantly, the IACtHR recognizes the heightened vulnerability of gender diverse persons during and after climate-induced disasters, who face a greater risk of gender-based violence due to stigmatisation and discrimination (para. 618). In discussing the need for adaptation measures, the IACtHR underscores that when evaluating climate impacts, vulnerability, and risk, States must rely on exhaustive data and identify the rights and groups of people that are particularly vulnerable, including women, girls, and the LGBTIQ+ community (para. 389). However, the Court does not provide further detail on the differentiated impacts suffered by this community in the context of the climate crisis, nor does it specify what kind of data supports adaptation plans. This is particularly important since data collection regarding impacts on LGBTIQ+ and gender-diverse communities in the aftermath of disasters is often overlooked and neglected (see here).

Women Environmental Defenders

The opinion also addresses the situation of women environmental defenders (para. 571-572), affirming that States must take special measures to protect them from threats, violence, and reprisals (para. 566). The Court calls attention to the gendered nature of violence and persecution faced by these defenders and links their protection to the obligations under both the American Convention and the Escazú Agreement (para. 564).