Despite its modest uptake since its inception in 2012, the European Citizens’ Initiative (ECI) has become the subject of several cases before the Court of Justice of the EU. The ECI is the world’s first and only instrument of direct transnational democracy, allowing a group of at least seven European citizens from seven different EU member states to request that the Union take new action.

As highlighted in two recent cases – Minority Safe Pack, which was decided last week, and End of Cage, which is currently pending –, the nature of ECI-related litigation has evolved significantly over time, reflecting deeper tensions about the instrument’s purpose and effectiveness. This piece provides a sobering perspective on the ECI, offering both legal and policy-based insights into its past, present and future applications and competing understandings as shaped by the Court’s case law.

The Evolution of ECI Litigation

In the early years, the Court was asked to review the legality of the Commission’s decisions rejecting the registration of some ECIs (e.g. Anagnostakis, Costantini, HB & others). Yet, more recently, notably since Puppinck, attention has turned towards the Commission’s follow-up obligations for ‘successful’ ECIs that reach the required one million signature threshold.

Two developments explain this evolution. First, the Commission’s registration policy has relaxed significantly, moving from the stringent standard set out in the original 2012 ECI Regulation to the more permissive approach introduced in the current 2019 ECI Regulation – a change largely prompted by the Court’s case law criticism of the former. Second, it is a testament to the organic emergence of the first batch of successful ECIs. Having reached the required threshold of one million signatures, a handful of initiatives began putting the instrument’s operation and effectiveness to the test. As a result, today’s litigation raises critical questions about the nature of the Commission’s obligations when confronted with successful initiatives. What type of response is the EU Commission legally required to provide to initiators of ECIs that have crossed the signature threshold? And how far can the Court go in reviewing the substantive adequacy of the Commission’s response?

Two recent cases exemplify this judicial scrutiny.

The Minority SafePack case, recently rejected on appeal, confirmed the established case law: successful ECIs merely ‘invite’ the Commission to propose legislation rather than creating a legally binding obligation to do so. Meanwhile, the pending case on the End of Cage ECI asks the General Court to go further by defining not only the substantive obligations but also the specific procedural requirements that the Commission must fulfill when responding to successful citizens’ initiatives. Ultimately, the case centers on two complaints: the Commission’s failure to provide updated legislative timelines as required by Article 15.2 of the ECI regulation, and improper denial of document access.

A Democratic Revolution Unfulfilled

The ECI represents the world’s first instrument of direct transnational democracy. Originating in the failed Constitutional Treaty and enshrined in the 2009 Treaty of Lisbon before becoming operational in 2012, the ECI marked a revolutionary shift in EU governance. For the first time, a right previously reserved for the European Parliament (under Article 255 TFEU) and the Council (under Article 241 TFEU) was extended to citizens themselves: directly requesting that the Commission propose EU legislation.

Article 10.3 TEU framed this as recognizing citizens’ rights “to participate in the democratic life of the Union,” fostering belonging and strengthening European community bonds. Suddenly, European democracy would not be confined to elections, but citizens could now collectively propose, support and participate in the legislative process itself, by potentially prompting it.

Yet despite positioning the EU as a pioneer in participatory governance, the ECI’s promise remains largely unfulfilled, leading to widespread disenchantment among citizens – a frustration now manifesting in the significant volume of litigation challenging the Commission’s responses.

A reality check reveals the scale of the ECI’s underperformance, leaving its democratic potential largely unexplored and untapped.

ECIs in low numbers

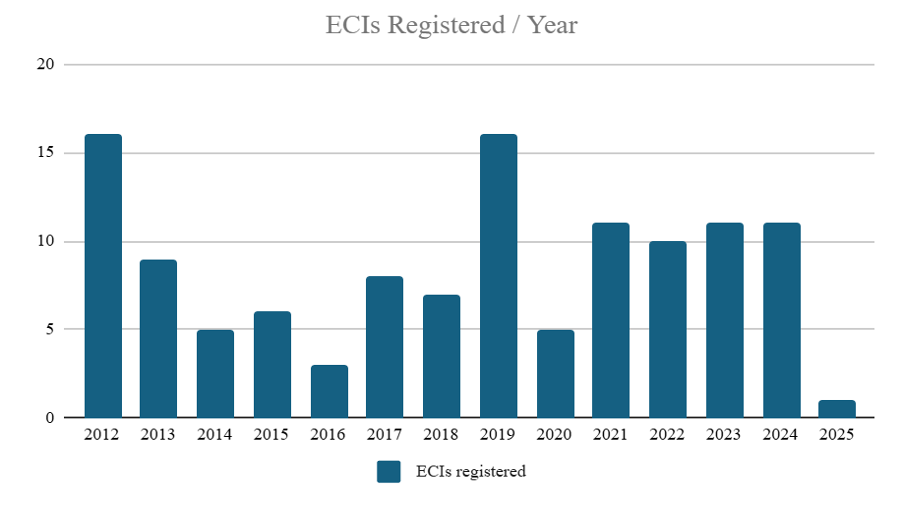

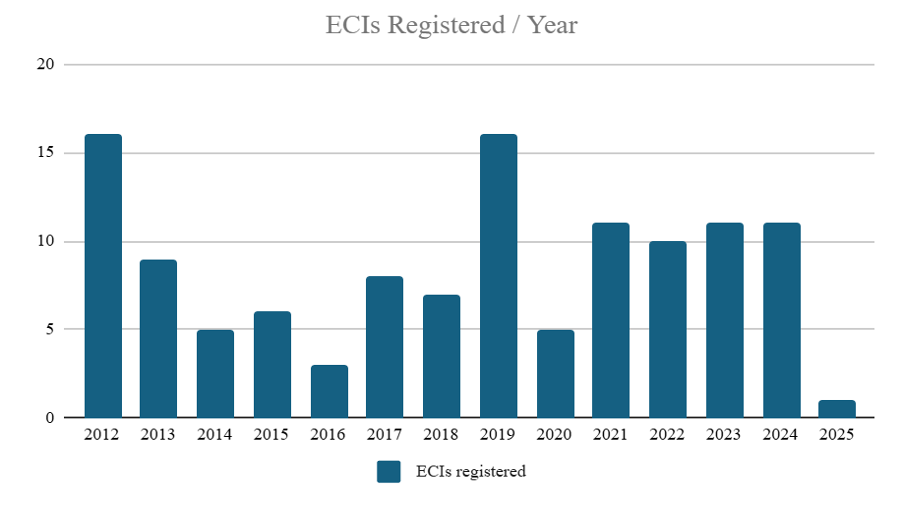

Since April 2012, the statistics tell a sobering story. EU citizens have registered 119 ECIs, with dozens more rejected on admissibility grounds, including the notable STOP TTIP, which led to the Efler case. Of these 119 registered initiatives, only 14 reached the one million signature threshold, representing a success rate of barely 11 percent.

This limited uptake explains why, after more than a decade, the legal nature of the instrument and the corresponding Commission’s obligations remain underdeveloped, poorly defined and, as a result, contested.

ECI’s Competing understandings

Today’s ECI operates under two fundamentally different and competing understandings of its nature and purpose. The first is an orthodox, formalistic understanding promoted by EU institutions that considers the ECI worthy of attention and follow-up only insofar as it complies with its formal requirements. The second is predicated on a pragmatic understanding, espoused by civil society, that perceives the ECI principally as a strategic, multi-purpose instrument for agenda-setting and political influence, the impact of which is decoupled from its formal validity.

These two conflicting interpretations of the instrument coexist in an ironic relationship: the pragmatic approach has emerged as a direct result of the limitations of the orthodox approach, as reinforced by the Commission’s practices, which were in turn shaped by the Court of Justice. While EU institutions adhere to procedural orthodoxy, civil society has learned to exploit the participatory potential and public visibility of the ECI to achieve political impact through alternative channels.

ECI’s Orthodox View

Under the formalistic approach, an ECI must be understood as a legal instrument that must meet all procedural requirements—from registration to validation of one million signatures—to merit attention and become eligible for impact. Even successful ECIs remain mere invitations that can be dismissed with limited judicial scrutiny, confined to checking for “manifest errors” as confirmed in Minority SafePack. This understanding, manifested in refusing over 30% of pre-2021 initiatives at registration, has historically constrained the instrument’s democratic potential, limiting its effective use to well-resourced organizations while discouraging broader participation.

This interpretation focusing on procedural compliance and formal thresholds reflects a legalistic interpretation that prioritizes institutional control over democratic participation. By maintaining high barriers and minimal obligations for follow-up, this understanding effectively confines the ECI from a participatory tool into a performative exercise with limited substantive impact.

ECI’s Pragmatic View

As a direct consequence of the orthodox approach spearheaded by the original Commission’s ECI practice, civil society has developed an alternative and pragmatic understanding of the instrument. This views the ECI as a multi-purpose mechanism for direct citizen influence on EU policy, which is inherently valuable, regardless of signature threshold attainment. This unconventional perspective sees ECIs as a useful instrument throughout the entire policy cycle. As such, it is not confined to the pursuit of agenda-setting, but can also attain multiple opportunities to exercise democratic participation rights. Under this view, ECIs can engage with EU policymaking at multiple stages—during the preparation of a Commission proposal, during co-decision by the Council-Parliament and even after adoption of new initiatives, to prompt ex post evaluations and induce the revision of existing legislation.

This approach recognizes that the major predictor of ECI impact is not formal Commission validation, but the ability to spark debate and influence priorities within the College of Commissioners and broader EU political space.

This pragmatic understanding stems from, and largely explains, the paradoxical fact that formally unsuccessful ECIs have often led to more legislative action than those that were successful. Thus, initiatives that never reached the formal threshold – and thus remain “unsuccessful”—have produced tangible policy results. One Single Tariff, which failed to gather sufficient signatures, nonetheless contributed to the elimination of international roaming charges (disclaimer: I was personally involved with my then students). Stop TTIP, rejected at the registration stage, mobilized unprecedented public opposition that ultimately contributed to the trade agreement’s abandonment, and to a new publicity regime surrounding the negotiations of EU trade agreements. Most strikingly, the Ban on Conversion Practices in the EU achieved inclusion in the Commission’s 2024-2029 political priorities within just four months of registration in May 2024, when it had collected only a few thousand signatures – well before reaching any meaningful threshold, let alone the million-signature target that it ultimately did.

Consider the stark contrast: despite crossing the one million signature threshold and triggering formal Commission obligations, no successful ECI has directly prompted the Commission to put forward a legislative proposal addressing its primary objectives. Even initiatives like Right2Water and SavetheBees, often cited as ECI success stories, achieved legislative outcomes only for secondary or tangential aims rather than their core demands.

This counterintuitive outcome reveals the fundamental disconnect between the orthodox emphasis on procedural compliance and the actual mechanisms of political influence within EU institutions.

This reveals how civil society has learned to use the ECI’s constitutional recognition and public visibility as a platform for broader political engagement, treating the registration process itself as an opportunity to generate media attention, build coalitions, and signal political priorities to Commission officials – regardless of whether the initiative ultimately succeeds in formal terms.

This pattern recognizes that the major predictor of ECI impact isn’t formal Commission validation, but the ability to spark debate and influence priorities within the College of Commissioners and broader EU political space.

ECI’s future is pragmatic

The pragmatic understanding of the ECI and its multi-purpose use is set to expand, by potentially leading to greater uptake.

In an era characterized by shrinking and often unequal institutional access and rising anti-NGO campaigns across Europe, traditional lobbying and advocacy pathways available to the citizenry and organized civil society have become increasingly constrained. Civil society organizations face growing restrictions on their activities, reduced funding opportunities, and heightened scrutiny of their operations in several member states.

Against this backdrop, the ECI has become the only direct channel of influence citizens have to shape the whole EU policymaking. Due to its institutional embeddedness, the ECI provides a “guaranteed platform” for citizen engagement that transcends national political volatility. Unlike traditional advocacy channels that depend on institutional goodwill or political access, this makes the ECI an increasingly valuable tool for civil society to maintain democratic participation even when other avenues are being closed off.

The ECI’s Coming Wave

The emergence and diffusion of this new pragmatic understanding is already showing signs of driving greater reliance on the ECI as a democratic tool. As civil society organizations increasingly recognize the instrument’s potential for strategic political engagement – regardless of formal outcomes – we can expect to see record numbers of ECI registrations in the coming years. This shift represents more than just increased usage; it signals a fundamental transformation in how citizens approach EU policymaking in the present political landscape. The most recent illustration is the Save Your Right, Save Your Flight ECI asking the EU legislator to maintain the level of protection guaranteed by the EU Passengers’ Rights Regulation.

The rise in ECI registrations, driven by growing demand for participation and influence, may eventually force the EU Commission and the entire EU institutional machinery to confront the instrument’s democratic significance. When faced with dozens or even hundreds of active ECIs simultaneously engaging with different aspects of EU policy – from security defence to housing, from climate action to social protection and migration –, the Commission will no longer be able to treat each initiative as an isolated procedural exercise to be managed and easily dismissed.

The sheer volume of citizen engagement is set to create a new dynamic where the Commission will be expected to develop more substantive and systematic approaches to ECI follow-up, not only because of existing legal obligations (as they will be refined by the Court’s case law) but also because of political necessity. This organic pressure from below might prove more effective than top-down regulatory reforms in forcing institutional adaptation.

Moreover, as the number of ECIs picks up, it will inevitably attract new constituencies to the ECI process—activists, advocacy groups, citizen movements and philanthropies – who previously viewed the instrument as too cumbersome or ineffective. These new users will bring fresh perspectives and innovative strategies, further expanding the ECI’s potential as a tool for democratic engagement.

This “democratization“’ of ECI use—where success is measured not by signature thresholds but by political impact— is long overdue, and carries the potential to finally realign institutional practice with the instrument’s original democratic aims. The Commission may find itself compelled to develop more meaningful engagement mechanisms, not because the Treaties require it, but because the political cost of dismissing widespread citizen participation becomes too high.

In this scenario, the emergent pragmatic understanding of the ECI does not just represent an adaptation to institutional limitations—it could become the catalyst for institutional reform, potentially transforming the ECI from a neglected and marginalized procedural tool into a central feature of EU democratic governance.

Conclusions

The growing legal challenges around successful but ineffective ECIs reflect a fundamental mismatch between constitutional recognition of participatory democracy and institutional realities. While the 2019 regulation improved accessibility, it failed to address the core disconnect between citizen expectations and the ECI’s capacity to produce legislative outcomes.

The Commission’s policy shift has merely transferred disappointment from registration to post-success follow-up, creating new forms of democratic disillusionment. Citizens who successfully navigate complex registration processes and mobilize one million signatures across multiple member states often find their efforts dismissed with minimal consideration.

As we await the Court’s decision in End the Cage Age, which will clarify procedural obligations, civil society is set to pursue its pragmatic understanding and use of this instrument. Rather than focusing solely on formal validation, future ECI strategies might prioritize building broader political momentum and strategic engagement with existing policy priorities – recognizing that democratic participation sometimes achieves more through informal influence than formal procedures.

If two competing understandings of the ECI coexist today in an ironic relationship is largely because the orthodox approach, as originally promoted by the Commission, has inadvertently created the conditions for a pragmatic use of the instrument to flourish. By severely confining the ECI’s use, the Commission has undeliberately pushed civil society toward more creative and potentially more influential uses of the instrument. The Commission’s and Court’s shared commitment to procedural orthodoxy has thus generated its own alternative, transforming the ECI from what institutions intended it to be into what democratic practice requires it to become.

As institutional access continues to narrow and the ECI’s Commission practice proves increasingly inadequate for meaningful democratic participation, a new pragmatic and unconventional understanding of the instrument is likely to become the dominant mode of ECI use, potentially completing the transformation of the instrument from a formal legislative mechanism into the primary avenue for strategic democratic engagement with European policymaking.

The post When Failure Succeeds and Success Fails appeared first on Verfassungsblog.